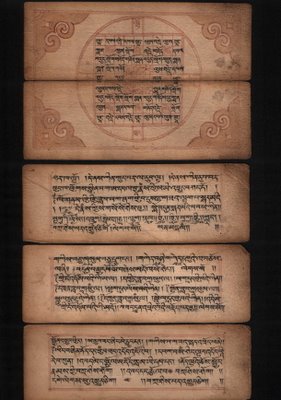

Breviary of an astrologer-lama

Most manuscript bundles from Mongolia can charitably be described as chaotic. Three of these represent my personal collection - it took me about the same number of days to put them in order and I am still left with loose leaves and incomplete works. The silk wrapping has also changed content a number of times. Although none of these texts are of particular interest, nor are they excitingly rare, the content of one bundle - had it been preserved in its original state - would yield a tremendous amount of information to the careful bibliographer such as the personal choice of the owner, most often requested liturgies, even the most often read works by a particular monk - something easily inferred by the amount of dirt on the edges if the paper is not worn enough.

I somewhat pretentiously dubbed this manuscript as an 'astrological' breviary and assumed it belonged to a person responsible for divination. Since I am completely incompetent in Tibetan astrology, the scrupulous study will be left to the interested reader.

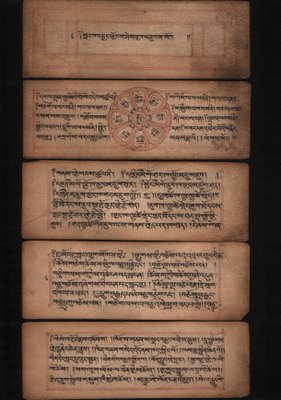

The title page presumably means 'phyogs bsgrigs' for phyogs, but this could equally refer to the auspicious and inauspicious 'directions' associated with the spar kha (Chin. ba gua) in the diagram stretching across 1b-2a, something a native of a given spar kha should either avoid or favour under certain conditions.

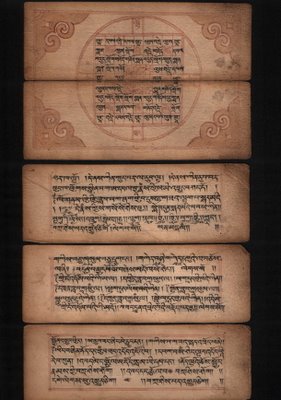

2b contains a simplified version of the dice-divination (sho mo 'debs) placed under the tutelage of Śrīdevī (Dpal ldan Lha mo) which is usually carried out with with three six-faced dice. Here only a single die is cast for a topic the outcome of which is predicted by the second 'register'. 3a-3b describes the positions assumed by a sa bdag, the Heavenly Dog, during different time-periods. The implications were probably well-known to the owner, this short list only serving as an aide-memoire. (Maybe I should read the Vaidūrya dkar po more often - this passage is still a bit obscure.) 4a and following continue in a similar fashion, such as favourable days to cure livestock (note that the camel stays at the head of the list), days to avoid the use of sharp knives (?; gri ngo for gri dngo), certain sūtras to be recited in correlation with the spar kha, the duodecimal animal-cycle correlated with the spar kha system as for days, and the concluding verse.

Blatant mistakes betray that the scribe was not intimately familiar with Tibetan: yas for yos, sprul for sbrul, pral for sprel, bshed for bshad, etc.; nor particularly careful: mjug for mgo (3a), bcos for bco (4a), etc. However, the illuminations seem to have been carried out tastefully.

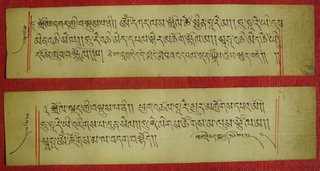

[Manuscript from Mongolia, currently in my private collection; Russian paper; Measurements: 167x57mm; Ff. 5, ill. 1b-2a, 2b. First image: 1a, 2b, 3a, 4a, 5a; second image: 1b, 2a, 3b, 4b, 5b.]

I somewhat pretentiously dubbed this manuscript as an 'astrological' breviary and assumed it belonged to a person responsible for divination. Since I am completely incompetent in Tibetan astrology, the scrupulous study will be left to the interested reader.

The title page presumably means 'phyogs bsgrigs' for phyogs, but this could equally refer to the auspicious and inauspicious 'directions' associated with the spar kha (Chin. ba gua) in the diagram stretching across 1b-2a, something a native of a given spar kha should either avoid or favour under certain conditions.

2b contains a simplified version of the dice-divination (sho mo 'debs) placed under the tutelage of Śrīdevī (Dpal ldan Lha mo) which is usually carried out with with three six-faced dice. Here only a single die is cast for a topic the outcome of which is predicted by the second 'register'. 3a-3b describes the positions assumed by a sa bdag, the Heavenly Dog, during different time-periods. The implications were probably well-known to the owner, this short list only serving as an aide-memoire. (Maybe I should read the Vaidūrya dkar po more often - this passage is still a bit obscure.) 4a and following continue in a similar fashion, such as favourable days to cure livestock (note that the camel stays at the head of the list), days to avoid the use of sharp knives (?; gri ngo for gri dngo), certain sūtras to be recited in correlation with the spar kha, the duodecimal animal-cycle correlated with the spar kha system as for days, and the concluding verse.

Blatant mistakes betray that the scribe was not intimately familiar with Tibetan: yas for yos, sprul for sbrul, pral for sprel, bshed for bshad, etc.; nor particularly careful: mjug for mgo (3a), bcos for bco (4a), etc. However, the illuminations seem to have been carried out tastefully.

[Manuscript from Mongolia, currently in my private collection; Russian paper; Measurements: 167x57mm; Ff. 5, ill. 1b-2a, 2b. First image: 1a, 2b, 3a, 4a, 5a; second image: 1b, 2a, 3b, 4b, 5b.]